What the heck is the volatile keyword and why use it

Problem

The result of some operation on shared resources by multiple threads can cause trouble as well as confusion sometimes. The following code is one of the examples:

// the static variable `stop` is shared by the threads started below

static boolean stop = false;

public static void main(String[] args) {

// started a new thread with the name of WRITE-THREAD

new Thread(new Runnable() {

@Override

public void run() {

stop = true;

}

}, "WRITE-THREAD").start();

// started a new thread with the name of READ-THREAD

new Thread(new Runnable() {

@Override

public void run() {

while (!stop) {}

}

}, "READ-THREAD").start();

}If one compiles and then runs this piece of code, most likely that it will terminated successfully. The READ-THREAD keeps executing the while loop if the stop is false. When the WRITE-THREAD sets the stop to true, the READ-THREAD should terminate immediately. Another possible executing process is that the stop is set to true even before the execution of READ-THREAD. It seems that this piece of code will never cause any trouble the programmer. However, in some rare cases, the program never terminates. What causes this unexpected result?

To make the problem more prominent, one can make the WRITE-THREAD sleep for a while before execute the stop = true; statement. Then the code of WRITE-THREAD becomes:

new Thread(new Runnable() {

@Override

public void run() {

try {

Thread.sleep(100); // block this thread for 100 ms

} catch (InterruptedException e) {

e.printStackTrace();

}

stop = true;

}

}, "WRITE-THREAD").start();Then re-compile and run the piece of code again. The problem surfaces. The execution of READ-THREAD is trapped inside the while loop. The expected the execution flow should be like this:

-

WRITE-THREAD and READ-THREAD are both started by the main thread and go into the

RUNNABLEstate. (Check out the enum classjava.lang.Thread.Statefor all the possible states of a thread except “running” state) -

The WRITE-THREAD starts to sleep immediately after it goes into the running state. And the READ-THREAD enters the

whileloop and keeps reading the value ofstop. (It doesn’t matter which thread goes into running state first because the final result is the same) -

When the WRITE-THREAD wakes up from sleep after 100 milliseconds, it will set the value of

stoptotrue. -

The READ-THREAD reads the value of

stopagain which istrueat this moment, and breaks the loop.

However, in reality, the loop continues. So the stop is never changed by the WRITE-THREAD. How is this possible?

In order to uncover the cause of this problem, we have to have a bit knowledge of how threads read and write the value of variables from memory.

When a thread takes a read/write operation on a value, the operation may happen either from main memory or the CPU cache used by the thread. The CPU cache used by the thread is local to the thread itself. The cache is used for performance considerations, so that a read/write operation can just occur in the cache rather than in the main memory which is more expensive for threads to perform such operations.

For a typical write operation, the thread writes to the CPU cache that is local to the thread first. And then the written value is flushed to the main memory. However, one cannot decide for sure that the flush occurs. Likewise, in some scenarios, the read operation may just occur in the cache for the read thread.

Think of this: the execution flow of a read thread is determined by a shared variable. Another thread changed to value of the shared variable but the change hasn’t been flushed to the memory in time. Or the change had been flushed to the memory, but for some reasons, the read operation reads the value of the shared variable from its CPU cache instead of the main memory. Unexpected results can surely arise from such a situation.

Back to our previous code. When the WRITE-THREAD starts, it goes immediately into blocked state due to the invocation of Thread.sleep(100). Now, the READ-THREAD goes into the while loop and stays in the loop. After 100 milliseconds, the WRITE-THREAD wakes up and updated the value of stop. Chances are the updated value, which is true now, is flushed to the main memory. But the while loop is so optimized that it just busy reading from its local cache and hasn’t had a chance to look into the main memory. So the loop never breaks.

Using the volatile keyword

The question is how can we guarantee that read/write of a variable is read from or written to the main memory instead of the CPU cache local to the thread that is operating on the value.

The answer is the volatile keyword. By declaring a variable as volatile, we tell the program any write operation to the variable should be immediately flushed to the main memory, and any read operation of the variable should read from the main memory instead of local cache.

The fixed code should like this:

// the static variale `stop` is shared by the threads started below

static volatile boolean stop = false;

// the following code...Run the code again. This time it is guaranteed to terminate.

Another way of describing the function of volatile is that volatile guarantees the visibility of the variable among all threads that operates on it. That is to say, any read/write operation on the variable is immediately visible to other threads. By “immediately visible”, we mean the change will be immediately flushed to the main memory instead of kept in any thread’s local cache.

Effect of declaring a variable as volatile

In fact, the volatile keyword has two effect.

- Guarantees the visibility of variable among threads.

- Prevent JVM from reordering instructions that involves volatile variables.

The first one is what we’ve seen above. Let’s talk about the second one.

In the above case, we mentioned that the visibility of volatile variable is guaranteed. However, this is part of the truth. In fact, all the write operations of non-volatile variables before a volatile write and all the read operations after a volatile read are guaranteed to be performed in the main memory.

Let’s see another example:

nonVolatileInt = 10; // suppose the old value is 0

nonVolatileStr = "world"; // suppose the old value is "hello"

volatileBoolean = true; // a volatile write (suppose the old value is false)if (volatileBoolean) { // a volatile read

System.out.println(nonVolatileInt); // output 10 (guaranteed visibility also)

System.out.println(nonVolatileStr); // output "world" (guaranteed visibility also)

}volatileBoolean = true is a write operation to a volatile variable. The changes of nonVolatileInt and nonVolatileStr are also flushed to the main memory simultaneously with the volatile write.

In the subsequent read, all non-volatile read occurs after a volatile read of volatileBoolean. All the values are read from the main memory. So the output to the console must be the updated value.

The ramification of this behavior is that instructions that involves a volatile read/write CANNOT be reordered. The volatile keyword prevents JVM from reordering instructions that involves a volatile variable. Because reordering of such instructions may change the behavior of the code. (In other cases, JVM may reorder instructions for performance reasons as long as reordering does not change the behavior of the code.)

nonVolatileInt = 10; // suppose the old value is 0

volatileBoolean = true; // a volatile write (suppose the old value is false)

nonVolatileStr = "world"; // suppose the old value is "hello"In the above code section, the visibility of nonVolatileStr is NOT guaranteed. Nevertheless, reordering before or after a volatile instruction are fine.

// though nonVolatileInt and nonVolatileStr are reordered, their visibility is also guaranteed after the volatile write of volatileBoolean

nonVolatileStr = "world"; // suppose the old value is "hello"

nonVolatileInt = 10; // suppose the old value is 0

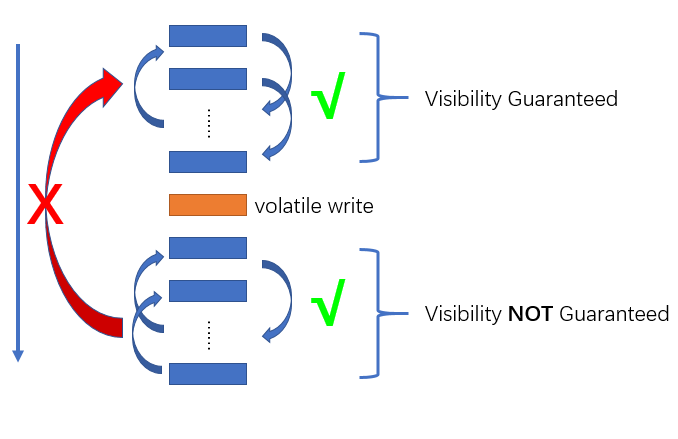

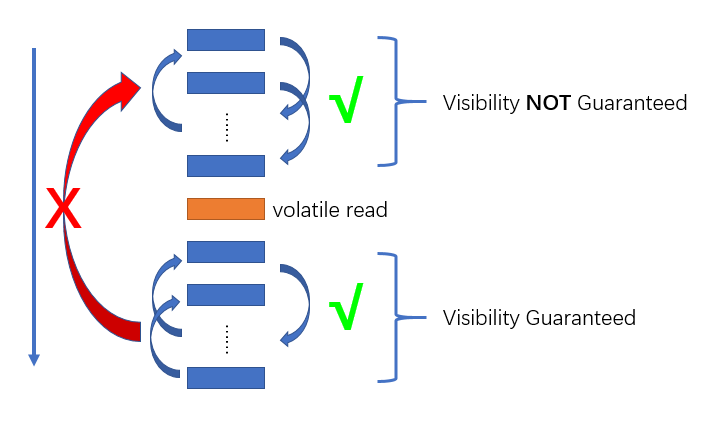

volatileBoolean = true; // a volatile write (suppose the old value is false)The following two figures illustrate the reordering rule.

In the above figures, suppose the program executes from top to bottom. Each rectangular block represents a instruction. The blue ones are instructions on non-volatile variables, while the orange ones are on volatile variables. All instructions before a volatile write/read can be safely reordered by JVM as well as those after a volatile write/read as long as JVM detects no change of behavior of the execution of code. Reorderings that cross a volatile write/read are prevented since it may change the behavior. All write operations before a volatile write are also flushed to the main memory with the volatile write. And all read operations that follow a volatile read read from the main memory.

In the piece of code that we mentioned first in this post, if we changed it to the following one, the program is also guaranteed to terminate.

static boolean stop = false;

static volatile boolean stop2 = false;

public static void main(String[] args) {

new Thread(new Runnable() {

@Override

public void run() {

try {

Thread.sleep(100);

} catch (InterruptedException e) {

e.printStackTrace();

}

stop = true;

}

}, "WRITE-THREAD").start();

new Thread(new Runnable() {

@Override

public void run() {

while (!stop) {

if (stop2) { // a volatile read

// `stop` is also to be read from main memory

// in the next loop

new Object(); // just do something here

}

}

}

}, "READ-THREAD").start();

}Thread safety not guaranteed

A misconception exists that volatile is used to deal the safety issues of multithreading. Well, in a sense, yes it is. Because multiple threads that are involved in the operations on a volatile read/write can be considered as directly happening in the main memory, since flushes between CPU cache and main memory occur immediately after any read/write operation on a volatile variable. The process of read/write and flush is indivisible. The visibility of the value of the variable is guaranteed among all threads. But it is important to notice that visibility is not the same issue as atomicity.

Application of volatile is useful when one deals with a single write thread and no less than one read threads. When more than one write threads are required, race condition can happen among different concurrently running write threads that writes to the same shared resource. Explicit synchronization using synchronized keyword or Lock from java.util.concurrent package to synchronize different write threads are necessary.